Search

Refurbishment of historic spaces

Re-enchanting

Villa Medici

How do you turn Villa Medici into a space that is receptive to contemporary knowledge, while still preserving the history and spirit of the place? As far back as 1833, Horace Vernet took a bold step by creating the “Turkish Room”, a reflection of an era fascinated by an imaginary Orient. In the 20th century, Balthus was the first to embrace a contemporary approach in the 1960s, followed by Richard Peduzzi in the early 2000s. A new chapter began in 2022 with Re-enchanting Villa Medici, a vast redevelopment campaign showcasing contemporary design, craftsmanship and the restored heritage of Villa Medici.

Over the past three years, 6 salons, 18 rooms and 2 gardens have been renovated.

In June 2025, six guest rooms and two citrus gardens, redesigned by architects, designers, crafts professionals and artists, have been inaugurated.

An architectural masterpiece of the Renaissance, Villa Medici has had several major renovations that have all contributed to its current identity. Conceived in 1833 by the painter Horace Vernet while he was Director of the French Academy in Rome (1829-1834), the Turkish Room was created just after the artist’s return from his first trip to Algeria. An Orientalist dream, it is an early example of an Islamic-inspired interior in the Eternal City, testifying to the fascination for an imaginary Orient shared by many European artists of the Romantic period. The decor in the Turkish Room blends Arab-Andalusian elements, Ottoman ornamental motifs, and naturalistic details on the vaulted ceiling. The colored terracottas covering the walls comes from the Giustiniani ceramics factory in Naples, and inspired Balthus for his painting The Turkish Room (Paris, Centre Pompidou).

Balthus (Balthasar Kłossowski de Rola, known as Balthus), painter and director from 1961 to 1977, refurnished the Villa Medici, designed a set of lamps bearing his name, restored the historic decor and invented a painting process that he applied to the Villa’s walls, producing a subtle patina effect with vibrant hues. The objective in his lengthy restoration campaign was to restore the palace, giving it the aura of a 16th-century villa. Far from conceiving a historical reconstruction, Balthus reinterpreted the decor, which showed his technical experience and artistic sensibility. The innovative solutions he experimented with at Villa Medici worked harmoniously with the Renaissance decor and took advantage of the natural light that bathed the rooms and altered their perception throughout the day. In the gardens, he rearranged the quadrangles, bringing in copies of antiques from Ferdinando de’ Medici’s collection, including the famous Niobides group.

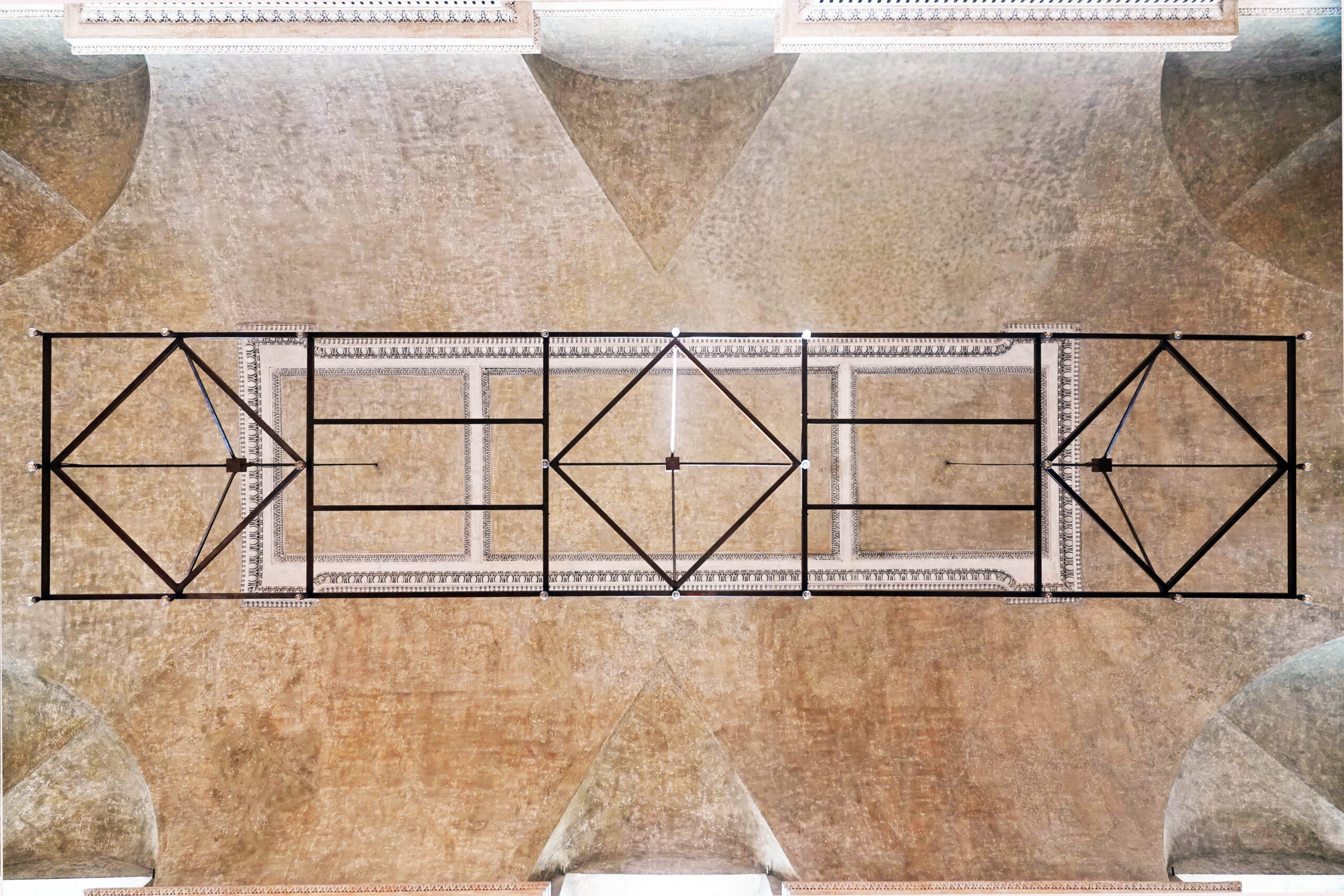

Richard Peduzzi, designer, scenographer and director from 2002 to 2008, designed the streamlined furniture for the entrance hall, cinema, library and cafeteria, opening Villa Medici’s doors to 21st-century design. In the gardens, he redesigned the parterre motifs with a play of geometries.

Using rough materials and simple lines, he created discreet, modern furnishings for the cultural and everyday activities at Villa Medici. His series of furniture and lighting fixtures has a utilitarian unity, blending into the space while fitting harmoniously with Balthus’ decor.

As part of his project to reorganize the spaces, Richard Peduzzi revisited the question of lighting in particular: he designed the chandeliers in the vestibule and Grand Salon, the floor lamps with square shades and the twisted concrete-iron lamps installed in the main staircase at the entrance.

On the garden level of Villa Medici, the refurbishment of the six reception rooms (2022) was entrusted to Kim Jones and Silvia Venturini Fendi, who selected contemporary furniture by French and Italian designers such as Chiara Andreatti, Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec, Noé Duchaufour-Lawrance, David Lopez Quincoces and Toan Nguyen, some of which were specially created for the occasion.

The refurbishment brings heritage into dialogue with contemporary furniture, such as the Via Appia table in travertine and chestnut, specially designed by Noé Duchaufour-Lawrance for Villa Medici, or the Grove & Groovy armchairs by Toan Nguyen, whose warm tones contrast with those of Chiara Andreatti’s Virgola chairs.

The re-enchantment of the salons has made it possible to restore and re-stage pieces from Villa Medici’s collections (a 17th-century painted armoire bought by Balthus, 18th-century tapestries from the Tenture des Indes), and to introduce an exceptional group of 20th-century tapestries on loan from the Mobilier National. These tapestries are by leading female artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Sonia Delaunay, Sheila Hicks, Aurélie Nemours and Alicia Penalba.

Moving upstairs at Villa Medici, the re-enchantment continues in a colorful, graphic idiom. In the six historic rooms above the loggia, Franco-Iranian architect and designer India Mahdavi orchestrated the refurbishment, playing with the juxtaposition of colors, materials, and geometries.

The Rooms of Jupier’s Loves, the Elements Room, and the Muses Room, which make up the former apartment of Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici, now open to visitors, are brightened with the pastel textiles chosen by India Mahdavi to upholster the antique furniture belonging to Villa Medici or on loan. Taken from the storerooms of the Mobilier National, such as the luminous suite of sofa and armchairs by Jean-Albert Lesage (1966) in the Lili Boulanger Salon with its luminous yellow. In the Muses Room, the large diamond-patterned carpet echoes the parterre redesigned in the 2000s by Richard Peduzzi, laid out in the gardens below.

Another allusion, the polychrome furniture of the Galileo and Debussy Rooms, designed by Mahdavi and covered with a marquetry pattern of trompe-l’oeil cubes, recalls the nuances of the sixteenth-century painted friezes and ceilings. Produced by Maison Craman Lagarde and the cabinetmaker Pascal Michalon respectively, these marquetry pieces are examples of the exceptional range of expertise mobilized for the re-enchantment of Villa Medici (cabinetmaking, ceramics, tapestry) and of the alliance, at the highest level, between design and arts and crafts.

In 3 years, 6 salons, 12 rooms and 2 citrus gardens have been refurbished.

6 guest rooms, by 6 teams of architects and designers working with art professionals

1 lemon garden, artistic direction Bas Smets in collaboration with Pierre-Antoine Gatier

1 parterre garden, with artists Natsuko Uchino and Laura Vazquez

Six teams of architects, designers, and contemporary artists, in association with arts and crafts professionals, were selected to rethink the layout of six guest rooms located in the south wing of Villa Medici. The refurbishment of the rooms is an opportunity to highlight a variety of exceptional craftsmanship in glass, metal, ceramics, wood, and plasterwork. The uniqueness of each room is reasserted: volumes are highlighted, surfaces sublimated (walls, floors), and the unitary coherence of each space emphasized. Most of the rooms, with an area of 40 m2 each, the rooms retain their original period structural elements: high coffered wooden ceilings, herringbone brick floors, double-leaf windows, and mezzanine.

The guest rooms have performed a variety of functions over the centuries.

In the sixteenth century, when Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici had the building fitted out, these spaces were used as furniture storage. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, when Villa Medici became the seat of the French Academy in Rome, they were converted into studios/living quarters for the fellows, a role they retained for over two hundred years. A walkway was then added to facilitate access. For a long time this accommodation was assigned preferentially to painters because of its dual north- and south-facing exposure, which offered spectacular views both over Rome and of the interior façade of Villa Medici. Since 2009, these living spaces have been open for booking and they now accommodate short-term guests.

The selection jury of the winning teams was composed of :

Alberto Cavalli (Homo Faber), Domitilla Dardi (Edit Napoli), Hedwige Gronier (Fondation Bettencourt Schueller), Hervé Lemoine (Manufactures nationales – Sèvres & Mobilier national), Christine Macel (Musée des arts décoratifs), India Mahdavi, Isabelle de Ponfilly and Sam Stourdzé (French Academy in Rome – Villa Medici).

The project STUDIOLO

Sébastien Kieffer and Léa Padovani, Paris, FR / Designers

Atelier Veneer: Romain Boulais and Félix Lévêque, Paris, FR / Concept developers-creators and cabinetmaker artisans

The project CAMERA FANTASIA

Studio GGSV: Gaëlle Gabillet and Stéphane Villard, Paris, FR / Designers

Matthieu Lemarié, Paris, FR / Decorative painter

Paper Factor: Riccardo Cavaciocchi, Lecce, IT / Micro-paper pulp artistThe project IL CIELO IN UNA STANZA

Studio Zanellato/Bortotto: Giorgia Zanellato and Daniele Bortotto, Treviso, IT / Designers

Incalmi: Patrizia Mian and Gianluca Zanella, Venice, IT / Grand feu enamelersThe project PARS PRO TOTO

Eliane Le Roux (Rocas), Brussels, BE / Artistic director and architect

Miza Mucciarelli (Atelier Misto), Brescia, IT / Architect

Claudio Gottardi, Brescia, IT / Master of decorative art

The project STRATUS SURPRISUS

Constance Guisset Studio : Constance Guisset, Paris, FR / Designer

Signature Murale : Pierre Gouazé, Puteaux, FR / Decorative plaster designer

Arcam Glass : Simon Muller, Vertou, FR / Master glassmaker

The project ISOLA

Sabourin Costes: Zoé Costes and Paola Sabourin, Paris, FR / Designers

Estampille 52: Paul Mazet and Fantin Mayer-Peraldi, Paris, FR / Cabinetmakers

The former secret garden of Ferdinando de’ Medici, with its triangular plan, has undergone several transformations since its creation, one of them on the initiative of Balthus, director of the Academy from 1961 to 1977, who introduced lemon trees. Landscape architect Bas Smets, in collaboration with Pierre-Antoine Gatier, chief architect of historical monuments, now proposes a new intervention to refine this pleasure garden in a contemporary spirit. New lemon trees are being planted in the ground itself and other trees in pots are being placed in the garden, while a pergola of Lunario lemon trees – a variety that produces fruit all year round – is being created. This pergola, 26 meters long, extends along the belvedere overlooking Rome, so that the skyline becomes an integral part of the garden’s layout.

Invited by Villa Medici, the Muller Van Severen designer duo created the Cosimo de’ Medici line of outdoor furniture, which integrates the garden. Produced by Tectona, this new line pays tribute to the Grand-duc of Tuscany, Cosimo I, Ferdinando’s father, who formed a collection of rare citrus fruits in Florence in the sixteenth century and passed on his passion to his son. With its triangular motifs, the Cosimo de’ Medici line echoes both the geometry of the garden and the architectural elements of Villa Medici. The color palette, composed of light green, dark blue, and white, reinforces the harmony at the heart of this citrus garden, offering a subtle contrast with the natural surroundings.

The piazzale, in front of the loggia of Villa Medici, extends to the parterre garden adjoining the Aurelian Wall, which marks the north-east boundary of the gardens. Subdivided into six compartments in a geometric design, the parterre offers an excellent view of the façade of Villa Medici, decorated with bas-reliefs from Ferdinando de’ Medici’s collection. To the east, it opens onto the Gallery of the Bosco, decorated with bas-reliefs embedded at the initiative of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. The gallery ends with the Balthus loggia, which housed the painter/director’s studio and which, before him, inspired Diego Velázquez’s painting View of the Gardens of Villa Medici, Rome (1650, Prado Museum, Madrid). In the sixteenth century, the parterre was the most ornamental part of the Renaissance garden, designed to be viewed from the windows of Villa Medici: at that time it displayed patterns of the rarest and most fashionable plants, finely designed and shaped, like embroidery. Ferdinando de’ Medici had a pink granite obelisk over six meters high installed there in 1583, the only Egyptian obelisk to feature in a private Roman garden at the time.

During the 1960s, Balthus had the parterre remodeled, favoring a refined arrangement that consisted of box hedges and lawns. He had copies made of the obelisk and the statues that adorned the gardens until the eighteenth century. In the 2000s, Richard Peduzzi designed the geometric motifs that have since become a hallmark of the gardens and that served in 2023 as India Mahdavi’s inspiration in her design for the enormous carpet in the Muses Room.

In dialogue with the scenographies imagined by Balthus and Richard Peduzzi, the parterre is now being enriched with a new intervention that combines garden art, decorative arts and contemporary creation. Surrounding the obelisk is a group of twenty lemon trees featuring a range of heirloom varieties, specially selected for Villa Medici by nurseryman and citrus grower Oscar Tintori (Castellare di Pescia, Tuscany). With a balance of contrasts between verticality and surfaces, the new layout revives the tradition of Tuscan citrus gardens.

From the 16th century, the gardens of the Medici became home to one of the leading citrus collections in Europe. In Rome, their introduction into the garden of Villa Medici is documented from 1579 and is closely linked to the creation of a long avenue crossing the estate, the Viale Lungo. Since then, ornamental citrus cultivation has evolved and expanded in three main forms: espalier cultivation, found on the two walls of the Viale Lungo (today the Viale degli Aranci), ground cultivation, which concerns the bitter orange trees planted in one of the garden’s square, and finally, pot cultivation.

It is this last cultivation that prevails for planting the twenty lemon trees in the parterre garden, in keeping with the Tuscan tradition, which favors trees with a “free” form, where the interior of the plant is pruned to allow light to penetrate.

The terracotta pots housing the lemon trees were produced by the Pesci Giorgio & Figli workshop using the famous Impruneta terracotta, particularly suitable for making garden pieces because of its frost-resistant quality. The craftsmanship of Impruneta, located south of Florence, is one of the region’s excellence traditions, with its origins dating back to the Middle Ages.

The ornamentation on the pots is an original creation by Natsuko Uchino, a Japanese ceramic artist based in France. The series she has created for Villa Medici comprises 20 unique pieces, decorated with motifs alluding to ancient iconography and to symbols of the Medici. The decorative work was carried out with incisions and various modeling and stamping techniques, particularly using molds of ancient bas-reliefs from the Bosco Gallery and fragments of Roman remains of the imperial period from excavations conducted at Villa Medici in the 2010s.

Natsuko Uchino develops a conceptual approach to the decorative arts, in search of transhistorical motifs. Her practice, drawing on the functional art tradition, lends itself here to offering an interpretation of objects conceived as real dwellings for living things. The reliefs on the pots, which are particularly abundant, accentuate their contemporary character and restore the memory of gesture.

The bases on which the pots rest were created by one of the last Roman stone carvers and marble workers who still works by hand. Indeed, Daniele De Tomassi specializes in working with ancient marbles, hard stones, and semi-precious stones. Inspired by the bases in the garden of Villa Medicea di Castello in Florence, those of Villa Medici were carved from peperino from Viterbo, a gray-hued volcanic stone, characteristic of Lazio. Their function is to drain water to prevent stagnation in the pot, which is harmful to the roots of the citrus trees.

Each of the 20 bases is engraved with a word, together forming a poem conceived by Laura Vazquez, poet, former fellow of Villa Medici, and winner of the 2023 Prix Goncourt for Poetry. The radical nature of her contemporary writing meets the materiality of the stone.

Partners and sponsors of Re-enchanting Villa Medici since 2022

Open the door to the Villa

VISITS

Step into one of the most beautiful Renaissance villas in the heart of Italy's capital and travel through Renaissance Rome, the Rome of the Grand Tour of the 17th and 18th centuries, and contemporary Rome....

Pack your bags at Villa Medici

ONE NIGHT AT THE VILLA

Sleep at Villa Medici, a unique place in Rome where Renaissance spirit and contemporary design come together.